The Arkansas Times turns 50 in 2024. To celebrate our golden anniversary, we’re looking back at the past half-century and sharing excerpts from some of our favorite pieces of reporting.

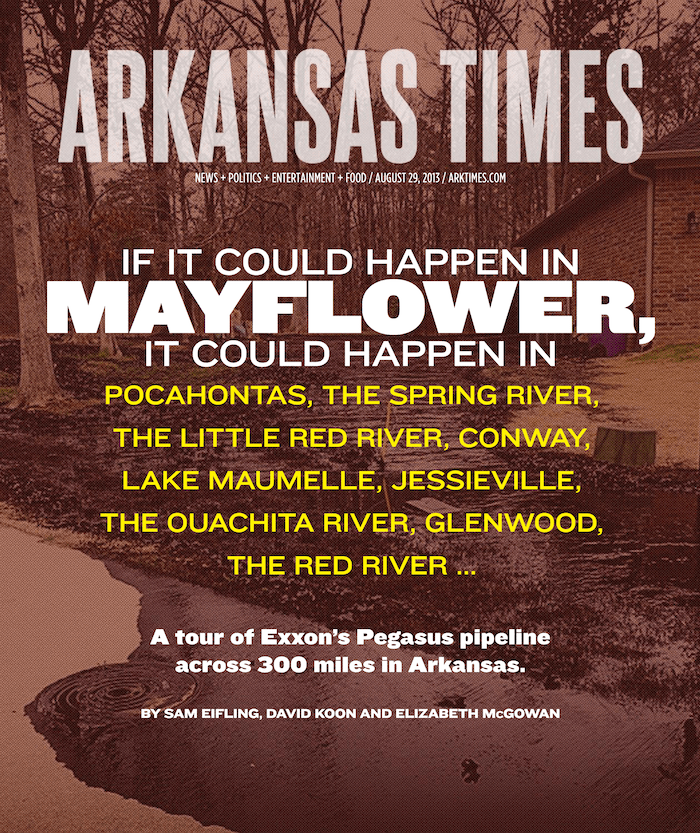

On March 29, 2013, an aging ExxonMobil pipeline called the Pegasus burst open behind a neighborhood in Mayflower, sending noxious fumes into the air and 210,000 gallons of crude oil gushing down suburban streets and into nearby wetlands. The spill was among the worst environmental disasters in recent Arkansas history. It came at a time when oil pipelines were in the spotlight due to controversy over the proposed Keystone XL project — which, like the Pegasus, was intended to carry notoriously dirty-burning petroleum from the tar sands of Canada south to refineries on the Gulf of Mexico.

The Arkansas Times lacked the resources to cover the Mayflower spill in depth, but then-editor Lindsey Millar had the idea — unusual at the time — to turn to crowdfunding. Together with the Pulitzer Prize-winning environmental publication InsideClimate News, we raised more than $25,000 in small donations to delve into the disaster and its aftermath, supplemented by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

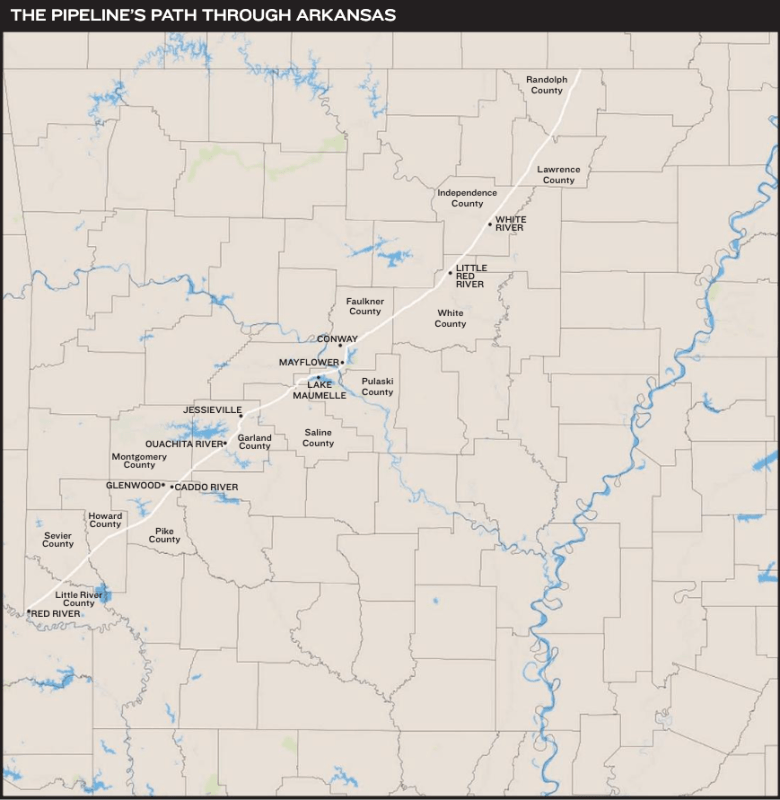

We reported on health concerns in communities hit by the spill, the ecological impact on Lake Conway, and the regulatory lapses that allowed Exxon to keep operating a 65-year-old pipeline with known defects. We profiled Mayflower residents whose lives were upended by a piece of infrastructure many didn’t even know existed. And we covered efforts to keep the Pegasus closed in light of the even worse disaster that very well could have been: Just a few miles southwest of Mayflower, the pipeline enters the watershed of Lake Maumelle, in places coming within 600 feet of the drinking water source for 400,000 people in Central Arkansas.

Just recently, on June 3, one of the last pieces of the Mayflower story fell into place when Exxon reached a tentative settlement agreement with the state and federal governments to pay $1.8 million for restoration of natural resources in the area affected by the spill. That’s on top of roughly $6 million the company paid the public in 2015 and 2019 for violating environmental law and failing to maintain the Pegasus properly (along with an unknown sum paid out in private settlements and litigation). For context, Exxon’s profits in 2023 were around $36 billion.

The Pegasus was shut down after the spill and has remained inoperative ever since. Exxon sold it to another energy company some years ago. But what happened in Mayflower in 2013 remains relevant — not only because the line could still one day be restarted, but because it’s a story that seems destined to play out again and again. Like the 2023 train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, that dumped 100,000 gallons of burning chemicals into the air of an unsuspecting community, the Mayflower spill revealed the costs of the unseen industrial infrastructure that crisscrosses the country. It’s easy enough to consider such random accidents a necessary price to pay for modern life — until your home is the one soaked in oil.

—Benjamin Hardy

“The path of the Pegasus“

In August 2013, five months after the Mayflower disaster, the Arkansas Times took a road trip alongside the Pegasus. Freelancer Sam Eifling, who has contributed to the magazine semi-regularly in the years since, teamed up with legendary Arkansas Times writer David Koon and Elizabeth McGowan of InsideClimate News to introduce readers to some of the communities along its 300-mile route within the state. Here’s a sampling of what they found. (Read the full story here, or peruse the August 29, 2013, issue in its entirety.)

The oil that erupted in Mayflower back in March began its trip in an Illinois hamlet named Patoka, 90 minutes east of St. Louis. It shot down ExxonMobil’s 20-inch Pegasus pipeline, under farms and forests, over the Mississippi River via a state highway bridge, through the Missouri Ozarks, across the Arkansas state line and, a few miles later, near the workplace of one Glenda Jones, whom you can find on a summer Saturday at her bar job, watching the Cardinals thump the Cubs.

The other bartender here at the Rolling Hills Country Club in the town of Pocahontas is named Brenda, so anyone visiting the golf course in far Northeast Arkansas is bound to meet one of the Endas, as they’re known around the club. At 5 p.m. it’s quiet in the 10-table lounge but for a Fox broadcaster making Jones’ day: “Molina deep … back to the wall … it’s gone!” Jones, the proud Enda and part-time house cleaner who refers to the Cardinals as “we,” hollers, “Yes, finally!”

Ask her about Pocahontas and she’s quick to tout its famous five rivers (the Spring, the Black, the Current, the Fourche, the Eleven Point). And the people are sure friendly. “Course they are,” she says. “We’re in the middle of the Bible Belt. Know what I mean? Everybody’s nice here.” If one thing gives her pause about this area, it might be the Pegasus. It runs right under her yard, and she worries about it rusting. “Stuff like that only lasts so long,” she says.

The Pegasus spill surprised many people in Mayflower, in part because many of them had no idea they were living atop an oil superhighway. So we got to wondering: Where does the Pegasus go? To find out, we traced its path using maps publicly available from the federal agency that regulates pipelines, the Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). We got precise with Google Earth, following the pipeline’s easement — the broad, bald line where trees are kept off the pipe — through the 13 Arkansas counties the Pegasus crosses on its way to Texas.

“If it burst, right here, right now?” asks Derik Fitzgerald, the voluble golf course superintendent, at the Endas’ bar. “What do you do?”

Fitzgerald knows and respects the Pegasus. Tuesdays and Thursdays Exxon flies a plane over to scope it out. One time Fitzgerald and another man on his crew were fixing an irrigation line maybe 40 feet from the pipe, on Hole 5, when Fitzgerald’s friend heard the plane turn. “He said, ‘That plane just seen us doing something.’ ”

They got a friendly visit from an Exxon rep after that one, just to be sure they knew to call in any projects within 200 feet of the pipeline. They also got a visit the time a flood piled branches and logs against the exposed pipeline in a creek. Fitzgerald called, and Exxon was out in a jiffy, yanking timber off the pipe and supervising the burning of the brush.

“I hate to take up for oil companies, I hate it,” Fitzgerald says. “But they seem like they’re on top of it.” When he needs to notify the company that he’s working near the pipe, Fitzgerald rings a guy. In his cell phone the contact reads “Billy Exon.”

The trip from the clubhouse to the Pegasus takes 5 minutes. Fitzgerald steers a golf cart down a knobby asphalt path, through hairpin turns between trees, and to the creek where the pipe is exposed, parallel to a little bridge. It’s a mottled, muddled thing, speckled with lichen and splotched with some tarry coating.

When the pipe was operating, 4 million gallons of crude would shoot through here at a pressure of 700 or 800 pounds per square inch. The crack that opened in Mayflower was some 22 feet long, roughly the length of this exposed segment. If there were another break, odds are people here would know it before the pipeline’s built-in remote sensors. PHMSA records show that of the 960 spills in the United States between 2002 and 2012, the general public reported 22% of them. Oil company employees found 62%. Sensors caught only 5%. That makes people like Jones and Fitzgerald part of the state’s first line of defense in a spill.

Fitzgerald heads back to the clubhouse for a Reuben with blue cheese dressing and to order a Miller Lite from Jones. As he picks his way through the trees he ponders life in Pocahontas. “Play golf and drink beer,” he says. “And call for a driver. … Thank God for wives. Understanding wives.”

THE LITTLE RED: Milepost 366

Lowell Myers apologizes for his murky river. “This is normally crystal-clear,” he says, but high rains have brought in mud from the hundred-odd upstream creeks that empty into this world-class fishery. Myers has guided here full-time for three years, and, for the 18 years before that, part-time while he managed the business side of Downtown Church of Christ in nearby Searcy. In the house of God, Myers spent his weekdays futzing with spreadsheets. He loved that job, but now he gets to guide people from all over the country, 12 months a year, on the river. “There’s a great quote, and I can’t remember what it is,” he says. “Something about being in church, thinking about God, and being outside, being with God.” Close enough.

Myers is heavyset, with an easy smile and snowy stubble that glints against deeply tanned cheeks. His flat-bottomed boat is 21 feet long and seats three comfortably. He backs it down the ramp at Ramsey’s Access, a launch point on the Little Red River downstream from Pangburn. A blue heron loiters on a log as Myers aims the boat downriver.

The river is low, and the pregnant clouds overhead suggest why. With so much flooding downriver, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers isn’t releasing water from Greers Ferry Lake — the impound that births this clear, cold current. Myers cranks up his outboard and steers around a slough. Cypress trees hunch along the banks, their knees jagging the shallows. A turtle slides off a log; dragonflies constellate overhead. It’s a summer Tuesday, and there’s not another person in sight.

These waters produced a world record brown trout once — 40 pounds and 4 ounces, caught by Rip Collins in 1992 — and remains a factory for brown and stocked rainbow trout. The river bottom’s rocky moss beds breed insects like caddisflies and blue-winged olives and sowbugs, which feed trout. The trout, in turn, feed people.

The banks of the Little Red are lined with floating docks that range from the ramshackle to the ornate. The fancier roosts have padlocked rod closets, barbecue grills, picnic tables. They carry etched wooden plaques with names like Lloyd’s Lodge and Lazy A Trout Dock.

Two dozen such platforms pass, then stillness. Myers points to a blurry smudge perpendicular below the surface, prominent enough to roil the current. There, two feet down, is the line of rocks that armors the Pegasus as it pierces the Little Red River.

“We call it the pipeline shelf,” Myers says. “It’s good fishing right behind it, where the water comes over and drops off over those rocks and into the deeper pool. Fish just hang out.”

Myers figures no one on the river connects this pipeline to the Mayflower spill. Despite the slouching yellow warning signs at the top of the bank, the pipe and the rocks that protect it are, to fishermen, simply another feature to navigate and exploit, akin to a manmade sandbar or boulder.

“I’ve been over that pipe, pshew, a hundred times,” he says. “I had no clue that was the same line as in Mayflower. And it could have easily been here instead of there. Why Mayflower instead of right in the middle of the Little Red?

“One rupture, one leak, one bad episode in a pipeline’s history, it could devastate our fishing industry.”

***

MAYFLOWER: Milepost 314.77

At sunset one evening, Ryan Senia, a displaced former resident of the Northwoods subdivision, walks around his side yard, and into a wide orange clayscape. This area used to be backyards, until crude swamped it and Exxon’s crews stripped away trees and exhumed tons of earth. “This is all new dirt,” Senia says over the thrum of a generator powering a tall light. He walks behind a neighbor’s empty home where the remnants of a former yard — a bike, a hose, a lawnmower, a propane grill, part of a birdbath — clutter the back porch. “Come up over here, you can see they’ve dug up under the slab,” he says. “You can see how deep they’ve dug it. So you know the oil is underground.”

He turns to another home’s foundation. There, in a grey puddle a foot beneath the brick, floats a glossy black blob the size of a fried egg. “It’s eye-opening to see the oil right there,” Senia says. “I know it’s not a large amount, but that’s only what you can see. The oil’s under the house.”

This is 20 weeks after the spill. Unified Command has cleared 19 of the 22 homes that were under mandatory evacuation as safe for reentry, Senia’s included, and Exxon notes that some people are moving back. By an informal count, maybe three homes are back to normal. Senia, for one, just sold his home to Exxon. At sundown on a weeknight, the driveways of Starlite Road North are blank, the windows are dark and all is quiet but for the generator and the yo-yoing moans of cicadas.

CADDO RIVER: Milepost 233.3

One of the few people in Arkansas who would see an instant upside in case of a disaster is a property owner on the Caddo, upstream of DeGray Lake. Frank Canale — loud, outspoken, tanned a uniform bronze — rents cabins in Glenwood, near where the Pegasus crosses the Caddo close to Mud Lake Road.

Originally from Memphis, Canale long made his living as an international real estate developer. He built the cabins on the Caddo when he came to Arkansas to care for his ailing mother, intending to sell them. Then the real estate market seized up in the credit crunch, trapping Canale in this Arkansas paradise.

His cabins on the Caddo, about 200 yards upriver from the pipeline, are picturesque: secluded, landscaped, with a terraced deck in the cool shade and steps that lead down to the waterline. The Caddo here lies in a cradle of stone rimmed by mountains, in a channel cut by a thousand-thousand years of flood. Most of the sunburnt paddlers who descend on weekends hail from Louisiana and Texas, he said, flatlanders craving trees and contours.

On a recent day, he was waiting to talk with someone from an auction company. He’s ready to cash out. He’s headed to Ecuador, he says, where some opportunities have opened. A spill? Why, that would certainly be one way out.

“Really, that would probably be my savior if that thing were to bust and wipe me out,” he says, laughing. “I’d probably get more from [Exxon] than I could ever sell the place for.”

A day later, up the river in Glenwood, Jim Smedley, owner of Arrowhead Cabin and Canoe, is shuttling canoeists back and forth in one of his white buses. A resident of Little Rock who flies helicopters for the National Guard, Smedley says he didn’t know the pipeline that ruptured in Mayflower also crosses the river he has floated dozens of times. A spill on the Caddo, he says, would be devastating.

“I understand we’ve got to have oil to function,” he says. “At the same time, if there has to be risk involved, there’s got to be some sort of inspection procedure. I’m not sure how they do it, but if that pipeline is that old, I’m sure it’s weak in a lot of places. There’s been land shift faults and everything else.”

Smedley says he’d like to think that Exxon and other oil companies would do the right thing to protect places like the Caddo River. But the spills in the Gulf and in Mayflower undermine that faith.

“I think the risk and the reward have to be balanced — the environmental impact,” he says. “I think they wait for something like this to happen to fix a problem they already knew about. Maybe they knew about it, maybe they didn’t. Maybe it was going to be too expensive to fix it.”