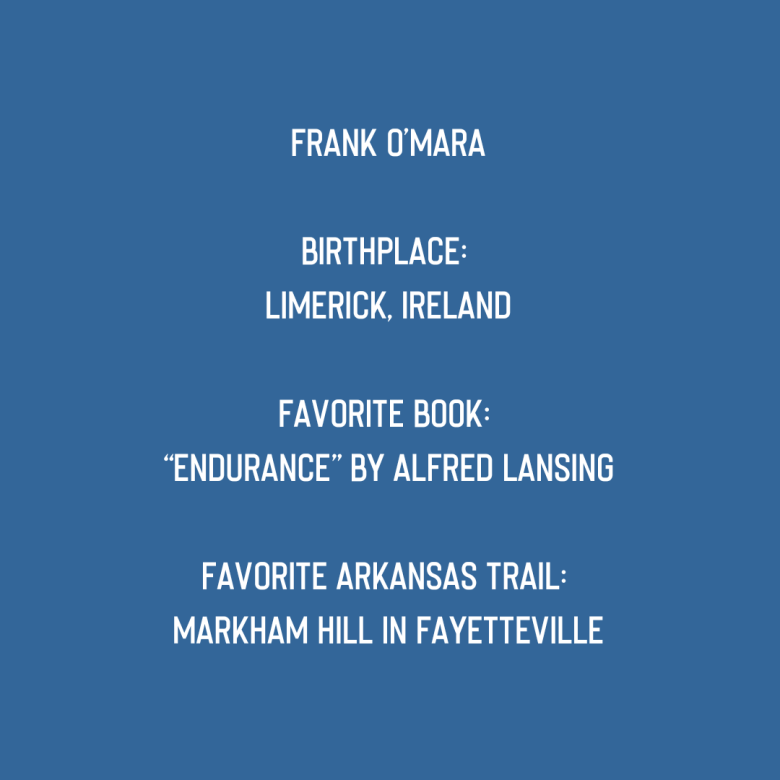

In 2010, former University of Arkansas track athlete and Alltel executive Frank O’Mara was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s disease. The diagnosis changed many things for O’Mara; he struggles with walking, speech and other tasks people often take for granted. What hasn’t changed, though, is his perseverance. In February of 2024, O’Mara released his memoir, “Bend, Don’t Break,” in which he shares lessons he’s learned from a storied life. “Victory is a life well lived or a day enjoyed,” is one of his favorite quotes, and a guiding principle.

Which coaches and executives have been your biggest inspirations?

I only ever had one coach, and that was John McDonnell, the much-celebrated UA track coach. But to answer your question, you can learn lots from people in one of two ways. You can learn what you should do from people, or you can also learn what you shouldn’t do, and that’s just as important a lesson as what you ought to do. I won’t name who I’ve learned what not to do from, though there is one person in particular I’m thinking of. Instead, I’ll say Scott Ford, who was the CEO of Alltel, and Jeff Fox, who was the president.

As a kid, you dreamed of being an explorer and wanted to travel to the South Pole. Just two years after your Parkinson’s diagnosis, you traveled to the Antarctic. What was that like?

Well, first, I needed someone to go with me to cross the Drake Passage from the tip of South America to the Antarctic. It took 48 hours, and the water can be very, very rough. So I talked one friend into it, but someone sent him a video of a rough crossing and he almost backed out on me. But when we got out there, onto what they call the Drake Lake, it was calm, three-meter swells and not 15-meter swells. … Ireland has a big history of polar exploration as a part of the Royal Navy, so just being an explorer was in my DNA, I guess. But I probably wouldn’t have done it if I hadn’t been diagnosed with Parkinson’s because I wanted to say, “I’m not just a cripple, I’m more.”

In “Bend, Don’t Break,” you largely omit your extensive running accomplishments, namely your World Championships and Olympic career. Was this intentional?

Particularly in Ireland, this is quite controversial, but I think it’s intentional. That’s always the headline, and my life now is about my struggle, rather than celebrating victories from 30 years ago. And honestly, I had a running career, but I also had a good business career as well. They were separate things, a job in short pants and a job in long pants. And then Parkinson’s, it’s a whole other career in itself. I had 14 years as a professional runner, 14 years in wireless, then 14 years with Parkinson’s. People often say you have three career cycles in your life. But the other thing that made me not focus on the victories is that you learn more from your failures than your victories, and looking back on moments I disappointed myself or my country, I say, “never again,” whereas with victories, you get all caught up in the celebration. You think more about the process with failure.

In your book, you talked about how Parkinson’s has slowly become a larger part of your identity. Has this changed how you view yourself, or how others view you?

I can’t speak for the latter, but as for myself, my self-worth has always been caught up in accomplishment. I think mowing the yard is an accomplishment; there’s very few things I can do now. It’s hard to say your happiness is directly proportional to your acceptance and inversely proportional to your expectations because your goals have to be moderated, but you have to have goals. For me, a goal might be making a phone call. That’s how bad it can become. So you go back into the now, but it can be quite frustrating. But you have to keep going.

What have you learned from running that helped you in this battle?

I struggle with that question because it’s all back to the failure answer again. I wrote in my book about it, we went to this big, big track meet once. I blew it the first day, I was beaten by about 30 yards, and the coach ignored me after. It was raining, and he drove the rest of the team back to the hotel. He left me in the stadium, but I didn’t know he’d left. I was in there with the swim coach, Sam Freas, and Sam looked after me. The next day, I was told I’d run the final leg of the relay again. I processed the previous day’s poor performance, and I was determined to make amends. I didn’t quite make amends, though; I got beaten by a hundredth of a second. I was 19, running against the record holder, who was 26. But I learned that you can steady the ship, and what’s important is that you do your best, not that you necessarily win.